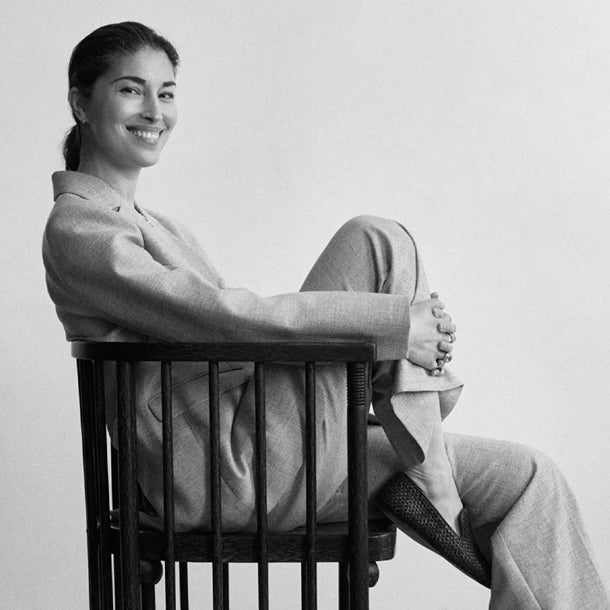

Next in our Conversations with Kynfolk series, we spoke to Grace Forrest, the founding director of Walk Free – an international human rights group working to accelerate the end of all forms of modern slavery. Walk Free is the creator of the Global Slavery Index, the world’s most comprehensive data set on modern slavery. Walk Free works with governments and regulators, businesses and investors, and faith and community leaders to drive systems change and partners directly with frontline organisations to impact the lives of those vulnerable to modern slavery. Recognising that lived experience is expertise, Walk Free works with survivors to build the movement to end modern slavery.

Grace is also a UN Goodwill Ambassador Australia, serves on the Global Commission on Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking and was the first Australian woman to win the Roosevelt Four Freedoms Award, Freedom From Fear. Her work is rooted in a deep commitment to social justice, and she continues to shine a light on one of the world’s most pressing yet often hidden human rights issues. We’re honoured to have Grace’s contribution to the AKYN Advisory Board.

In this conversation, we explore the realities of modern slavery within the fashion industry today, and how we can bring human rights to the forefront of the conversation.

Q: Walk Free has done critical work on exposing forced labour and you’ve previously described modern slavery as “woven into the fabric” of our global economy. What does that mean for the fashion industry in particular?

A: Fashion is one of the top five global industries for instances of modern slavery. From cotton fields to garment factories, supply chains are riddled with risk factors for forced labour: poverty, gender inequality, lack of legal protections, exploitative recruitment practices, and opaque sourcing systems that allow abuse to go unseen.

Walk Free defines forced labour as situations where people are coerced into work through violence, intimidation, debt bondage, or deceptive recruitment, with no means to leave. In the fashion industry, this manifests through withheld wages, unsafe conditions, threats, and the exploitation of already marginalised communities — often women and migrant workers. When I say it’s “woven into the fabric” of our global economy, I mean exploitation has been normalised and made invisible in the way global trade operates. Fast fashion’s business model depends on relentless speed and ultra-low prices, which are only possible through a race to the bottom for wages and conditions. A T-shirt shouldn’t cost less than a sandwich when — on average — over a hundred pairs of hands have touched that garment, from the growing of the cotton to the final stitch.

Q: Many consumers are now asking where their clothes come from. Is transparency enough, or does fashion need to go further?

A: Transparency is a necessary first step, but it’s not the finish line. Knowing where your clothes are made is important, but what matters just as much is how they’re made and whether the people behind them are safe, paid fairly, and working in dignified conditions. Too often, brands release glossy transparency reports while continuing to source from suppliers linked to labour abuse. True accountability means going beyond disclosure to action – addressing power imbalances in supply chains, ensuring living wages, and creating grievance mechanisms that workers can safely access. The goal should be not just to trace problems, but to fix them.

Q: How do we balance individual responsibility – like ethical shopping – with the need for systemic, legislative change?

A: Both are essential, but they function differently. Ethical shopping can be an important personal stance and a way to support better practices, but it won’t dismantle exploitative systems on its own. We have to avoid placing the burden of fixing global supply chains on individual consumers, especially when information is incomplete and options limited. That’s where legislation comes in. Binding laws – like modern slavery reporting acts, import bans on goods made with forced labour, and mandatory human rights due diligence – are needed to hold corporations accountable. Individual actions should fuel collective advocacy for these systemic changes. Ethical fashion isn’t just about what’s in your wardrobe; it’s about what you’re willing to demand from those in power.

Q: There’s often a focus on sustainability from an environmental perspective. How can we ensure human rights aren't sidelined in that conversation?

A: Human rights and environmental sustainability are two sides of the same coin – you can’t have one without the other. Yet too often, the conversation around sustainability gets reduced to materials and carbon footprints, ignoring the human cost of production. We need to intentionally centre workers in these discussions. That means including garment workers and cotton farmers in decision-making processes, acknowledging that climate impacts disproportionately affect vulnerable communities, and ensuring that transitions to sustainable materials or practices don’t leave workers behind. Ethical fashion isn’t truly sustainable if it protects the planet but exploits the people who live on it.

Q: What gives you hope right now in the fashion space?

A: The uncomfortable truth is that ethical brands remain the exception, not the rule.

But I will always be inspired by the growing leadership of workers, grassroots organisers, and consumers who are refusing to accept business as usual. From garment worker unions in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka to Indigenous-led cotton initiatives, people on the ground are pushing back against exploitation and carving out better futures for themselves and their communities.

Brands - like AKYN - who are genuinely willing to interrogate their practices, partner with communities, and build new, ethical models for production, remind me that fashion can be a powerful force for dignity and justice when it chooses to be. Fashion’s power lies in its influence, its creativity, and its global reach. It should be leading on human rights, not lagging behind.

Meet our Advisory Board.

Photographer: Trisha Ward

Grace wears our Rocia Washed Black Coat, Peace Jumper and Sol Straight Jeans.

Read more

As CEO of Textile Exchange – a global non-profit accelerating action on climate and nature across the fashion, textile, and apparel industry – Claire Bergkamp is helping to lead the global fashion...

For the latest in our Conversations with Kynfolk series, we spoke to sustainability strategist, systems thinker and writer, Rachel Arthur, who we are thrilled to have as a member of the AKYN Adviso...